How to make a good decision

Mark Fryer

How to make a good decision

Albert Einstein was once asked if he had only one hour to solve a problem what would he do?” He said: “I would spend 55 minutes trying to understand the question, then I wouldn’t need any more than 5 minutes to find the solution.”

Consider how many corporate meetings we have been party to where those present, including ourselves, have lost sight of the desired outcome, engaging in interesting conversation and debate, as opposed to keeping a laser focus on the original problem to solve.

This powerful concept, of really getting under the skin of the question before attempting to find the solution, requires great discipline and is a difficult habit to instil.

Our research has shown that the key is to distil the key question into the following structure: A closed question beginning with ‘do’, with personal accountability (I or we), complete with specific ‘where and/or when’ details.

e.g. Do we want to open an office in Fife this year?

Suggesting it should be a closed question may feel counter intuitive because open questions create interesting discussion and that’s the point, we don’t want interesting discussion we want decision.

The closed question will require a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer, or, as we discovered, there is a third answer - yes, no or the next best alternative. Our ‘trilogy of answers’ model joins up with the system 1 or system 2 parts of our brain which we discussed in our last article.

So many models, how do they work together?

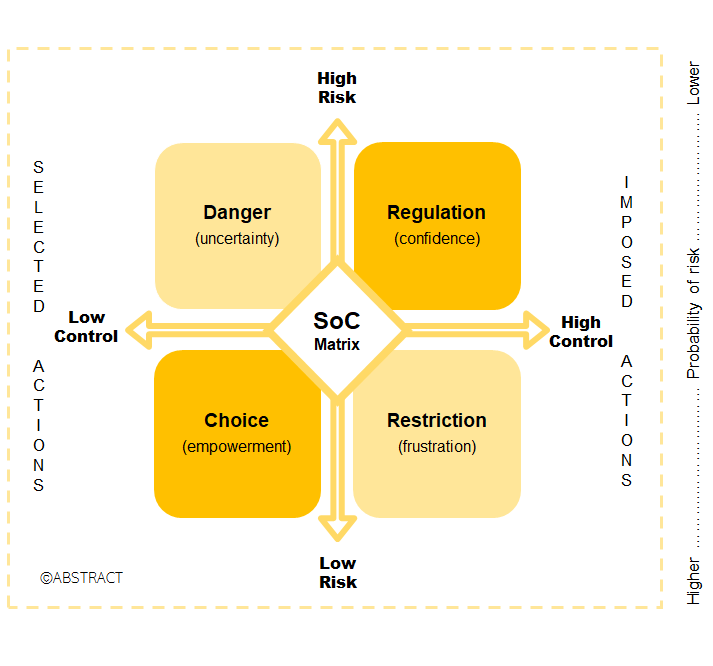

In the last article on How to form sound judgement, we shared our Spectrum of Consequence (SoC) model.

The quadrants Regulation and Restriction, on the right, both have high control and therefore the answer to the closed question is not a trilogy of answers but simply binary - ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

For example, it’s 5.55pm and you’ve parked your car in an area that has its parking restrictions lifted at 6pm. A traffic warden asks you to move your car otherwise you will get a ticket. You stress that it’s 5.55pm and surely the warden can show some discretion. No, these are the rules! The question – do I park my car here at 5.55pm and risk getting a ticket? No. It is binary question and System 1 takes care of this. In light of no discretion by the warden, you drive off avoiding a ticket but feeling very frustrated. High control/Low risk = frustration!

The quadrants Danger and Choice, on the left, have low control and therefore we can apply the ‘trilogy of answers’ theory.

For example, on January 15, 2009, Captain Chesley Sullenberger (Sully) and co-pilot Jeff Skiles took off from LaGuardia airport in an Airbus A320 with a full quota of passengers. As you would expect, even with thousands of flying hours between them they were operating in the Regulation (confidence) quadrant. Seconds after take-off they suffered a catastrophic bird strike which wiped out power in both engines. They moved uncontrollably to Danger (uncertainty). Sully had not benefited up to this point from ABSTRACT personal development but his system 2 kicked in.

The question…..Do I try to land this aircraft with no power at LaGuardia airport?

1. Yes – they would hit a skyscraper killing everybody on board and innocent civilians.

2. No - they would hit a skyscraper killing everybody on board and innocent civilians.

3. Best alternative – I could try to land it on the Hudson River and we might survive.

Thankfully, he chose the ‘best alternative’ and successfully landed the aircraft on the river with everyone on board surviving with only a handful suffering minor injuries.

Remember our traffic warden from the earlier example operating in Restriction (frustration)? What if they had moved themselves left into Choice (empowerment) and used their judgement, instead of the system, and made a ‘best alternative’ decision along the lines of “please park here, though may I ask you stay with your vehicle and at 6pm you can leave your vehicle as the restrictions don’t apply”. What a difference that would have made!

So far, in this series of articles, we’ve covered Character and Organisational Character. We’ve introduced our Spectrum of Consequence model to support better judgement. We have taken inspiration from Albert Einstein and formed the key question around the desired outcome, and we’ve used the trilogy of answers to make a better decision.

Next time, in a special bonus article, Decision Making - A Practical Guide, we’ll take the topic of decision making a stage further and look at the logical decision making model guaranteed to create best outcomes - and the troubling dynamics of group thinking.